#47: reverse-engineering the workflow of a scientist explaining the pandemic

thinking about journalism as a practice, not as a profession

In This Issue:

📌 An interview with Katelyn Jetelina, Your Local Epidemiologist

💡 How might we define the practice of journalism in an age when anyone can inform the public?

Good morning,

Over the pandemic, independent writing by scientists and other data-oriented experts has become an increasing fixture of my news diet. Two favorites are Emily Oster, the economist who writes about pregnancy, parenting and the pandemic and epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina, who writes about Covid-19 and other public health issues. Their newsletters are well-written and sourced, and easy to understand. Both are on Substack, though countless others I follow on Twitter and Instagram.

Every time I see their posts, I find myself wondering: How does this person work? Do they consider their work to be journalism? Because it certainly occupies the “news” bucket in my diet. How do they have the guts to inform the public? What checks and balances are they using?

So I reached out to Dr. Jetelina to ask these questions and more. She has been writing Your Local Epidemiologist for two years now, originally on Facebook, now on Substack and she has hundreds of thousands of subscribers.

I told her I wanted to try to reverse-engineer what she’s doing to understand how someone becomes a confident and responsible public-informer. She was generous and open about her process.

Our conversation is below.

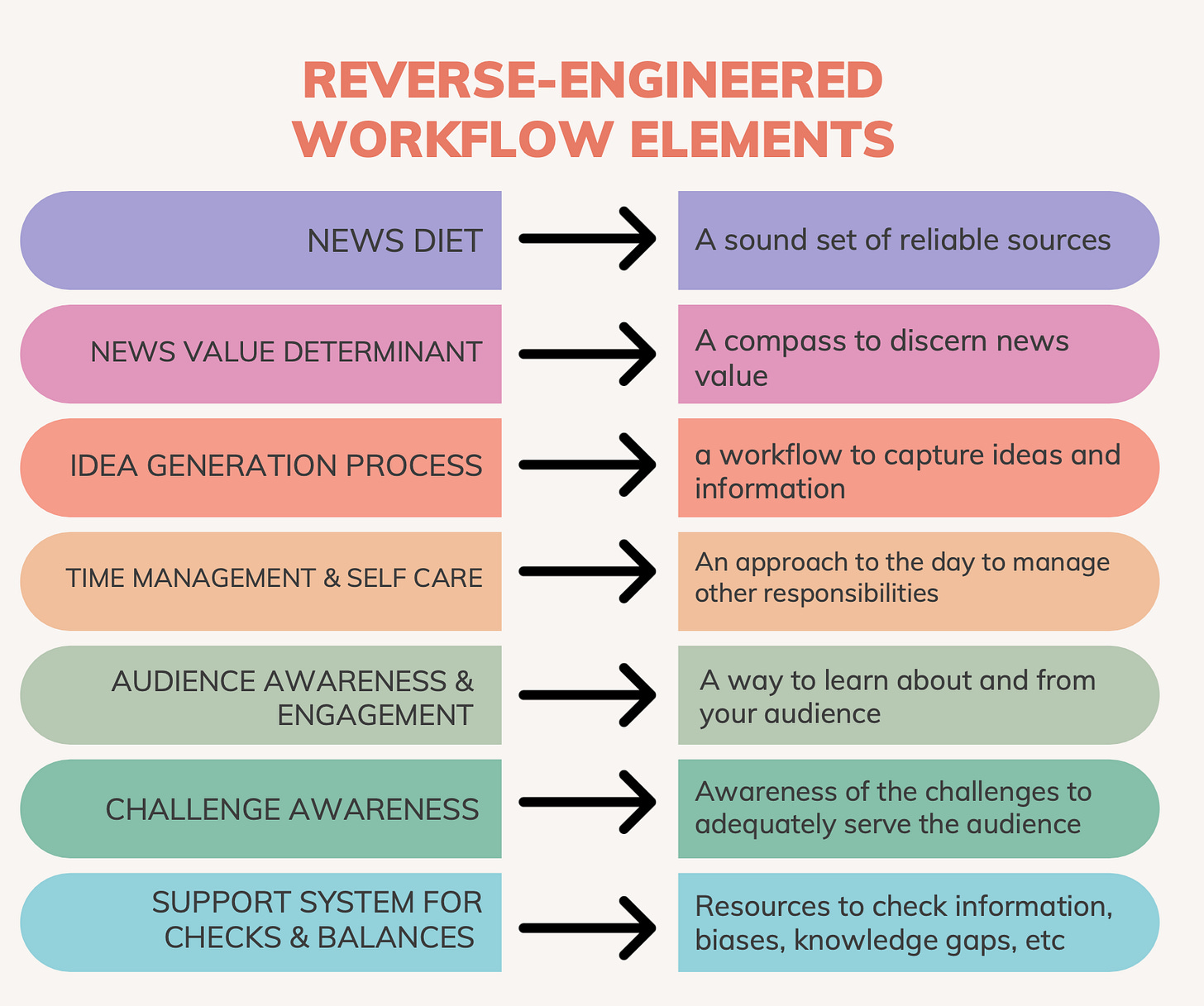

Here is a preview of what I see as some key ingredients of an effective workflow. Today’s “how might we” prompt builds on this chart, so it appears again at the end. I recommend reading the interview before spending too much time with it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

When and why did you start Your Local Epidemiologist?

Katelyn: It all started back in March 2020. I started giving an update just through a regular email to faculty, staff, and students about what was going on with the pandemic. I called them my daily data-driven updates. They were just literally a few sentences every day of what was going on. A few days later, one of my students asked me to start a Facebook page so she could start sharing the posts with her family and friends. And so it started off with, I don't know, 30 faculty and a few of my students in my class, and started growing and growing and growing on Facebook. I pulled the data I think last month and it looked like I have a reach of about 130 million people since March 2020.

It's really been an organic network of people interested in hearing, directly from a scientist, what is going on with the pandemic? Substack came along in February 2021, almost a year after I started the Facebook page because my Facebook page was hacked by anti-vaxxers. And so I quickly recognized that social media is a place we rent space from rather than own it. I felt hopeless. I couldn't get any of my content back. I was introduced to Substack and so I started posting on there. And even after I got my Facebook page back, I continued to just have that as my primary mode.

Do you intend to continue indefinitely or is this a timelined project?

Katelyn: You know, I don't know. I sent out a survey to my readers in October 2021 [which 72,000 people took] just to ask them who the audience was because I had no idea who was reading my stuff.

I also asked them if they're interested in anything beyond a pandemic, public health wise. I think about 96% said yes, it just depends on the topic. And so I've started dabbling in some other things like mental health and other infectious diseases. I'm seeing where it goes and being flexible. I'm trying to sustain public interest in public health beyond the pandemic and the effectiveness with which I do that is yet to be determined.

Could you walk me through a typical day of news/information consumption?

Katelyn: It's definitely changed over the past two years. I would definitely say it has been refined because I have so many hours in the day. So the first is Twitter. I follow a lot of scientists on Twitter. The second is mass media. I depend on four or five pretty solid new sources like The Atlantic, The New York Times, NPR, who are really good at breaking news, and sometimes include links to scientific articles that I might not have found. And then the third is this thing called Nerdy Neighborhood. It's this Slack channel that we created [during the pandemic] among us scientific communicators who share information as well.

How do you navigate the writing process? How do you decide what you need to synthesize or address?

Katelyn: It's a good question. Honestly, I think it's only possible because I've been doing this from the beginning. I know exactly what puzzle pieces are missing, where, and so when we get a new piece of information, I know exactly where it fits in this massive puzzle.

One of the reasons I really like Substack is because I just create drafts. So for example, I have a draft about long Covid and anything I find interesting, any article or tweet or whatever, I just place in there. Or, for example, antigen tests, I'm writing a post about that tomorrow. Like, what are all the new studies saying about antigen tests and Omicron? And so when I need a topic or have time to write, I just open one of those and start synthesizing the evidence that I've already collected and trying to create a story of how the science has evolved.

What is the trickiest thing to navigate when you're writing a post?

Katelyn: So the thing that's most challenging but I think makes me effective compared to other scientists is how to translate the science to laymen. And that's a really difficult line to dance on because you don't want to lose too many nuances or you're not doing right to the science, but you need to lose enough words to be understandable and actionable for the public. And so I think that's [what I’m] most cognizant of when I'm writing.

How do you view your audience? Knowing how scientifically literate they are or aren't, where their biases or discomforts might lie…it sounds like a lot to navigate.

Katelyn: Yeah. I honestly had no idea, so this is why I created a survey in October. I mean, I knew that my emails opened for about 400-500,000 people, but I didn’t know who those people were. And I was really surprised about some of the results. It was very bi-partisan. I had people across the spectrum, for social and fiscal politics.

Also, for example, [52%] of readers had a graduate degree or higher. And so going off of that… I knew I had a very educated group. They were just educated…not in my science. And so it made it actually a lot easier trying to describe [for example] what a viral load is.

I do know that I lose people. I mean, I think that's part of being a good science communicator. I listen, I read the emails, I read the messages that people send to understand where I'm losing people and where I'm not. And that also helps shape the content as I go.

If you need to check the facts on something, or you’re not sure you understand what you've read, what sort of checks or balances do you rely on?

Katelyn: I lean a lot on that Nerdy Neighborhood. It's multidisciplinary. There's policy researchers, there are MDs, more epidemiologists like myself, there’s virologists, there's immunologists. That's a group of about 30 of us who I've leaned on a lot throughout the pandemic and couldn't do it without them. And if someone helps me substantially, I write them as a coauthor of the Substack and I ask them to have a second look at it.

How do you plan your frequency of posts?

Katelyn: It's honestly not pre-planned. I kind of just start writing or I see something in the news or I'm curious about something and then I start digging into it and push it out. I will say, though, with the waves of the disease, or the increase, my posts increased because there's a lot more anxiety and interest among people. And then they subside, like last summer.

Recently, I’ve been trying to get on a cadence because I have now a copy editor and a translator. And so in order to not burn them out, I need to give them some sort of cadence.

I have noticed that experts on substack and other platforms don’t stick to a consistent editorial schedule, which has made me wonder: do we have to be consistent [in the way editorial operations have been for the sake of their business model] or can the needs just drive the content? Content for content’s sake is not always the best idea.

Katelyn: It's a really interesting question. And I'd be curious to see data on it because there's certainly a point where I can understand there's too much frequency. I'm sure there's science behind that too.

What do you feel are the key educational (in school or out of school) experiences you have had that have led to you feeling confident in your ability to do all this sifting and synthesizing and communicating for the public? In my experience, most scientists aren’t comfortable with this process.

Katelyn: I don't know if I'm comfortable doing it. I definitely get stage fright when I start thinking about the numbers that this newsletter reaches and I consistently have to bring myself to just be like, hey, what would I just be telling my mom, my sister, and a few of my colleagues? I really have to refocus on that or it gets too overwhelming.

I mean, I’ve never had training in scientific communication. I got my Bachelor's in science, I got my Master's in epidemiology, I got my PhD in epidemiology and then my postdoc and I went to faculty. I never took a class about dissemination or communication ever. And I think that's the problem right now. It's not just me, but every scientist. We don't know how to talk to the public.

I figure it out every day by listening to feedback from people. Over the past two years, I've learned so much about scientific communication, all the way from, “Hey, you should be more inclusive and say pregnant people instead of pregnant women,” or “This color scheme is much easier to read on graphs for the colorblind.” These little things that I never realized before. And I think what has benefited me is I'm open for constructive criticism. I really am. I want to learn how to do this.

The other thing is, I am a professor. I love teaching. I absolutely love teaching. And so I kind of look to this as: this is a lecture. This is me teaching the public one-on-one. And it seems to be working, I guess.

One thing I feel I've learned during the pandemic is that when it comes to scientific information, the ability to update your understanding of something when new information is presented to you is the million dollar skill that most people don't have. But most scientists do have it. Is that just part of the scientific method? Has anything supported your ability to develop this skill?

Katelyn: I think it's kind of a combination of the two. I'm trained, formally trained, in thinking this way. I'm formally trained in knowing that we don't know anything. And every little piece of new information just adds to this puzzle. It adds to the picture. And we have to pivot in order to be smart. And I think that you're right. That's something that the majority of people aren't trained in and that's what they find so frustrating during the pandemic—how quickly the science changes and our knowledge changes. And that's actually a good thing. If it wasn't, I would be incredibly nervous right now.

So there's that, formal training in science, and also I get a ton of encouragement from people that this is helpful. That seeing behind the curtain can help in some capacity to understand what all the chaos is about. And so I think the combination of the two, and me also just enjoying it, makes me want to continue.

I understand you have young kids. How are you making time to do this? From the perspective of someone who wants to get better at consuming to be able to better educate their family and friends but they are super busy: how do you structure your time?

Katelyn: I think the word you used is important: structure. I knew I had to find a cadence to do this so it didn't overwhelm my life. And so what that looked like for the past two years is, in the morning, just open up Twitter, see what's new, get the girls ready, put my phone down, work, pick up the girls and once they are asleep, write and consume. And having to be very mindful of the two separate spaces so it doesn't take over my life because it very easily could. Some days it does. That's when a really good support system is absolutely necessary. And some days it doesn’t and I feel like I can juggle it pretty well. But it is very challenging.

Do you see yourself as a journalist? Why or why not?

Katelyn: No, I don't see myself as a journalist. I see myself as a scientist trying to educate people along the way. I guess I don't see myself as a journalist because I don't interview people. I just look at the science and try and distill it down to a language that's understandable to the layman. For some reason, I think of a journalist as interviewing for different perspectives and that's not necessarily what I'm doing right now.

Here is a fun fact about interviews that I just learned from The News Media: What Everyone Needs to Know:

Interviews did not become part of journalism until the nineteenth century and then in the United States before anywhere else… For a long time, interviewing was regarded as undignified…Why was interviewing judged to be pernicious? Well, it was just plain unseemly… “Public men,” as the phrase of the day had it, were normally of high status and social pedigree. Journalists were typically far from it. Anyone could become a journalist. But the relative classlessness of America—compared to Europe—made resistance to the interview more feeble in the United States than in the Old World…

For European critics of interviewing, journalism was a calling to be practiced by people with high literary ambitions. The model form of the newspaper article was an essay—it was normally an analysis of (rather than a report of) current political and economic events. It was more likely to be undertaken from a private study than from a newsroom.

Katelyn: Very fascinating. So I guess I'm like an old European journalist.

Note, if you’re wondering about the $: YLE is a paid newsletter. Since Katelyn has a full-time job though, it’s not her primary source of income. She chose her subscriber strategy by essentially copying what historian Heather Cox Richardson did.

Quick Synthesis:

Here are my quick notes on the journalistic process described above, which turn into the reverse-engineered workflow chart we will discuss below in the “How Might We” section.

The reality is, whether people want to call themselves journalists or not, much of what we see online comes from journalistic practices. As I’ve written before, it’s really hard to distinguish between what counts as journalism and what doesn’t. The only clean argument for something being journalism or not would require us to say that journalists need to have a special degree or be employed by a newsroom to do journalism. They don’t.

Still, we are wading our way through murky waters of all sorts of disseminators of information. Some are doing their best to be responsible. For that category of independent disseminators of news-related information, I pulled what I heard in Katelyn’s interview into this list.

I think it’s a pretty solid starting point for a responsible public information practice. There are certainly things we could add to it.

So, today’s design prompt asks: How might we define the practice of journalism in an age when anyone can inform the public? Journalism as a practice, not as a profession.

What would you add to this list?

Happy Thursday,

Jihii